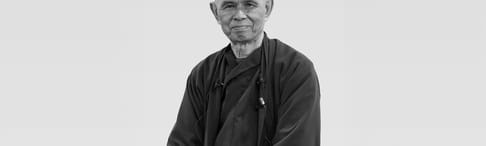

Thich Nhat Hanh

1926 - 2022

Known around the world as a spiritual leader, poet, peace activist, and the “Father of Mindfulness”, Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh is renowned for his powerful teachings and as a best-selling author on mindfulness and peace.

How to Pronounce Thich Nhat Hanh

The English pronunciation is: Tik · N’yat · Hahn. However, since Vietnamese is a tonal language, this is only a close approximation of how one would pronounce it in Vietnamese. By his students he is affectionately known as Thay — pronounced “Tay” or “Tie” — Vietnamese for “teacher.”

Early Life

Thay was born on October 11, 1926, into a large family in the ancient imperial capital of Hue in central Vietnam. His father Nguyen Dinh Phuc was from Thanh Trung village in the province of Thua Thien, Hue, and was an official for land reform in the Imperial Administration under the French. Thay is the 15th generation in the “Nguyen Dinh” line. The most distinguished poet in 19th Century Vietnam, Nguyen Dinh Chieu, author of the epic poem Luc Van Tien was Thay’s ancestor, belonging to the 9th generation of the “Nguyen Dinh” line.

It is customary in Vietnam to write the family names first (Nguyen Dinh) before the given name.

Thay’s mother, Tran Thi Di, was from Ha Trung village, in Gio Linh District, in the neighboring province of Quang Tri. Her Dharma name — her spiritual name as a Buddhist — was Trung Thinh. She received this name and the Five Precepts from Thay’s teacher (together with Thay’s father) at Tu Hieu Temple when they came to visit their son right after Tet (Lunar New Year) in 1947.

Initial Buddhist Inspirations

Thay was the second-youngest of six children, with three older brothers, an elder sister, and a younger brother born soon after him. He lived until aged five with his extended family, including uncles, aunts, and cousins, at the home of his paternal grandmother — a large house with a traditional courtyard and garden, with a lotus pond and bamboo grove, within the old imperial city walls.

When Thay was four, his father was assigned to work in the northern province of Thanh Hoa, about 500 kilometers north in the mountains. A year later, the family moved up to join him. As a boy, Thay began to eagerly read the Buddhist books and magazines brought home by his elder brother Nho, whom he loved and admired. He registered for a nearby informal homeschool, with the family name “Nguyen Dinh Lang.”

In his later talks and lectures, Thay often recalled a pivotal moment when, perhaps as early as age nine, he was captivated by a peaceful image of the Buddha on the cover of one of Nho’s Buddhist magazines. The illustration of the Buddha sitting on the grass, naturally at ease and smiling, captured his imagination and left a lasting impression of peace and tranquility. It was a stark contrast to the injustice and suffering he saw around him under French colonial rule. The image awakened a clear and strong desire in him to become just like that Buddha: someone who embodied calm, peace, and ease, and who could help others around him also be calm, peaceful, and at ease.

A year or so later, Thay and his brothers and friends were talking about what they wanted to be when they grew up. His elder brother Nho was the first to say he wanted to become a monk. The boys discussed it for a long time and finally all agreed to become monks.

The magazine was called Duoc Tue (“Torch of Wisdom”). This story is told in Thich Nhat Hanh’s book A Pebble for Your Pocket: Mindful Stories for Children and Grown-ups (2001).

Thay later said, “During that discussion, it was clear that some decision or some aspiration was there very strong in me already. Inside, I knew that I wanted to be a monk.”

This story was told in Thich Nhat Hanh’s June 8, 1992 Dharma Talk.

About six months later, at the age of 11 and on a school trip to a nearby sacred mountain, Thay had what he would later describe as his first spiritual experience. As his fellow schoolmates sat down to eat, he slipped away to explore alone, eager to find the old hermit rumored to live there. He didn’t find the hermit but, hot and thirsty, came upon a natural well of fresh, pure water. He drank his fill before falling into a deep sleep on the nearby rocks.

The experience created a profound feeling of satisfaction in the young boy. Having found the water, he felt completely fulfilled. He felt that he had somehow met the hermit in the form of the well, and found the best possible water to quench his thirst.

A sentence came to his mind in French: J’ai gouté l’eau la plus délicieuse du monde (I have tasted the most delicious water in the world). The wish to become a monk continued to grow in Thay’s heart, and a few years later that dream would be realized.

The story of the sacred mountain, the hermit, and the natural well was compiled from the following sources: Thich Nhat Hanh Q&A at Brock University, Toronto, 15 August 2013; Thich Nhat Hanh Q&A in Plum Village, July 19, 2009; Thich Nhat Hanh Q&A in Vancouver, Canada, August 12, 2001; The Hermit and the Well by Thich Nhat Hanh, (2001); Cultivating the Mind of Love by Thich Nhat Hanh (1996) pp.11-13; and Thay’s 1993 Dharma Talk: “Cultivating our Deepest Desire”.

The mountain in Thanh Hoa is known as Nui Na (“Na Mountain”). The story of the Nui Na hermit appears in the writings of Nguyen Du, the renowned 16th Century Vietnamese poet, and may have been based on the true story of a royal official in the Tran Dynasty, who retreated up into the mountain in the 14th Century. More information here.

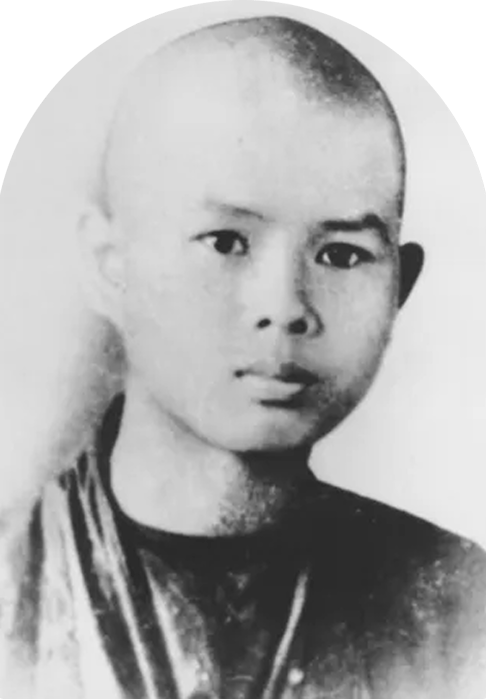

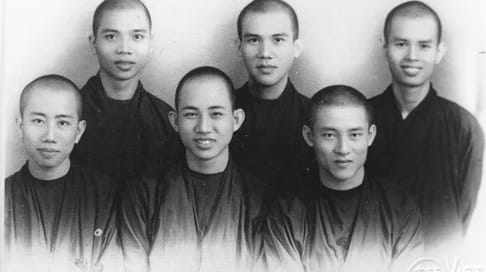

Novice Training Begins

In 1942, at the age of sixteen, with his parents’ permission, Thay returned to Hue to begin novice training at Tu Hieu Temple, under Zen Master Thich Chan That (1884-1968), entering the Vietnamese Zen Buddhist tradition in the lineage of the renowned Master Linji (Rinzai) and Master Lieu Quan.

Thay’s teacher, Thich Chan That, belonged to the 41st generation of the Linji School (臨濟宗, Vietnamese: Tông Lâm Tế, Japanese: Rinzai) and seventh generation of the Lieu Quan Dharma line. Zen Master Thich Chan That had the Lineage name Thanh Quý 清季; Dharma name Cứu Cánh 究竟; and Dharma title Chan That 真寔.

According to Vietnamese Buddhist tradition every practitioner receives a lineage name when first committing to practice the Five Precepts; on becoming a monk they receive a monastic Dharma name. Later, monks may take or be given by their teacher or community one or many Dharma titles, marking the development of their career. Every monastic member in the Vietnamese Buddhist tradition has a name which begins with Thích, which represents the Buddha’s family name “Shakya” (釋迦). It can be considered a family name or surname for Buddhist monastics in Vietnam.

After three years of instruction, Thay formally received the novice precepts in the early morning of the full moon of the ninth lunar month of 1945 (21 October). He was initially given the aspirant name “Sung” and was known as “Điệu Sung.” Điệu means “aspirant” and Sung comes from the words sung túc, meaning “prosperity” or “to prosper.” When he received the Five Precepts he was given the Lineage name Trừng Quang (澄光, “Calm Light”), marking his generation in this particular Buddhist school; and when he received the Ten Novice Precepts, he was given the monastic Dharma name Phùng Xuân (逢春, “Meeting Spring”), the name by which was known in the temple.

Note: The story of Thay’s novice years come from his book My Master’s Robe (2002).

Monastic Training: Traditional Roots

Despite the tension beyond the temple walls, with the Japanese occupation of Vietnam (1940-45), and the scarcity of food during the catastrophic 1945 famine, Thay recalled his novicehood as a happy time.

His years at Tu Hieu Temple were a time of rustic simplicity. There was no electricity or running water and no toilets. As a young novice in training, his daily tasks included chopping wood, carrying water from the well, sweeping the courtyard, working in the garden, tending the cows, and, when the season came, helping to harvest, thresh, and mill the rice. Whenever Thay had a chance to be his teacher’s attendant, he would wake before dawn to light a fire and boil water to prepare his tea.

The temple followed the Zen principle of “no work, no food,” which applied to everyone from the highest monk to the newest member. In the spirit of the Zen lineage of Master Linji, Thay was taught to become fully present and concentrated in every task, whether washing the dishes, closing the door, sounding the temple bell, or offering incense at the altar. He was given a little book, Essential Vinaya for Daily Use* — forty-five short verses in Sino-Vietnamese which he had to memorize and recite silently during every act of daily life to maintain concentration.

Thay witnessed at close hand the Japanese occupation and Great Famine of 1945. Stepping out of the temple he saw bodies out in the streets of those who had died of hunger, and witnessed trucks carrying away dozens of corpses.

The story above is compiled from the following sources: A 24 July 2012 Plum Village Q&A session, Call Me By My True Names: The Collected Poems of Thich Nhat Hanh (1999), and My Master’s Robe (2002),

Thay’s description of the Great Famine of 1945 is from a 12 October, 1997 interview with Don Lattin for The San Francisco Chronicle.

* Essential Vinaya for Daily Use (毗尼日用切要) compiled by Vinaya Master Duti (讀體, 1601-1679), also known as Jianyue Lüshi (見月律師). Thay also studied the Ten Novice Precepts and the Twenty-Four Chapters of Mindful Manners by Master Zhourong, and the Encouraging Words of Master Guishan. The meditation he learned as a novice in Tu Hieu Temple was from the Tiantai school.

Monastic Training: During the First Indochina War

When the French returned to reclaim Vietnam in 1945, the violence only increased. Although many young monks were tempted by the Marxist pamphlets’ call to arms, Thay was convinced that Buddhism, if updated and restored to its core teachings and practices, could truly help relieve suffering in society, and offer a nonviolent path to peace, prosperity, and independence from colonizing powers, just as it had during the renowned Ly and Tran dynasties in medieval Vietnam.*

In 1947, Thay’s teacher sent him to study and live at the nearby Bao Quoc Institute of Buddhist Studies in Hue. His studies took place against the backdrop of the First Indochina War (1946-54), as, following the withdrawal of the Japanese, a violent struggle emerged between the French forces and the nationalist Viet Minh engaging in guerrilla warfare to end colonial rule.

Over 50,000 people would die in the fighting, as the Vietnamese fought for the kind of independence India would win from the British. The skirmishes and violence did not spare the monks or temples. They became a place of sanctuary and refuge for revolutionaries fleeing the French.

Although unarmed and nonviolent, many monks, including some of Thay’s close friends such as Thich Tam Thuong , were shot and killed. French soldiers frequently raided the temples, searching for resistance fighters or food. Thay vividly recalled one raid where soldiers demanded the last of their rice.

At Bao Quoc, Thay continued to read progressive Buddhist magazines which explored ideas for a “socially conscious” Buddhism that was concerned not only with transforming the mind, but also the wider environment and conditions in society, including the economic and political roots of poverty, oppression, and war. For example, Tien Hoa Buddhist magazine published articles on the importance of studying science and economics in order to understand the actual roots of suffering, and not rely only on chanting and prayer.

The story elements above were compiled from the following sources: My Master’s Robe (2002). Thich Nhat Hanh’s letter, “The Magical Sound of the Sitar,” October 13, 2009, Inside the Now (2015), and At Home in the World: Stories and Essential Teachings from a Monk’s Life (2016).

Unfortunately the Bao Quoc Institute’s records are no longer extant. They were deliberately burned in 1975 and what remained was lost in a later accidental fire.

In addition to Tien Hoa magazine, Thay was also inspired by the writings of Zen Master Thich Mat The (1912-1961) and the author Nguyen Trong Thuat (1883–1940). Both figures saw the deep riches in Vietnamese Zen history and the capacity of Buddhism to bring about “a new spring” for Vietnam, the kind of Buddhist renewal also being proposed by other reformers and modernists elsewhere, for example, the Chinese Master Taixu (1890-1947). Thich Mat The studied with Master Tinh Nghiem (Qing Yan) in China, and brought back his ideas to Hue.

*For more on Thay describing being tempted by the communist path himself, see the Mindfulness Bell, issue #34, Autumn 2003.

Monastic Training: Seeking a New Path

In late spring 1949, after two years at the Bao Quoc Institute, 23-year-old Thay left Hue with two other monks and a friend to further their studies in Saigon.

As battles were still raging, they took a long route, and in parts travelled by boat to avoid the military roadblocks. Along the way, the young monks decided to affirm their deep aspiration to become bodhisattvas of action by taking new names. They all took the name Hanh, meaning “action.” In this way, Thay (Phung Xuan) became Nhat Hanh (“One Action”). As the name of every Vietnamese Buddhist begins with Thich, so it was that, from this time, Thay became known as Thich Nhat Hanh.

When they arrived in Saigon, the war with the French was still going on. Thay and his friends stayed and studied at a number of other different temples, for weeks or months at a time, while they pursued their self-directed studies. Thay soon published his first books of poetry.

Tieng DIch Chieu Thu (“Reed Flute in the Autumn Twilight,” a collection of fifty poems and a play in verse) published under the name Nhat Hanh by Dragon River Press (1949). This was followed by Tho Ngu Ngon (“Fables”), published under the pen name “Hoang Hoa” by Duoc Tue publishing house (1950). Anh Xuan Vang (“The Golden Light of Spring”), was published in 1950.

Capturing his experiences of war and loss, his poetry was well received and his poems were considered some of the best examples of Vietnam’s new and influential “free verse” poetry movement.

From this time, he established a reputation first and foremost as a poet rather than as a monk or teacher — a real distinction since for centuries poets had been esteemed figures in Vietnamese culture and society.

In autumn 1950, Thay helped co-found An Quang Pagoda, a new temple built of bamboo and thatch. It would later host a reformist Buddhist institute where he would become one of the youngest teachers, and is today one of the most prominent temples in the city. It was there that Thay received the Bhikshu precepts the following year.

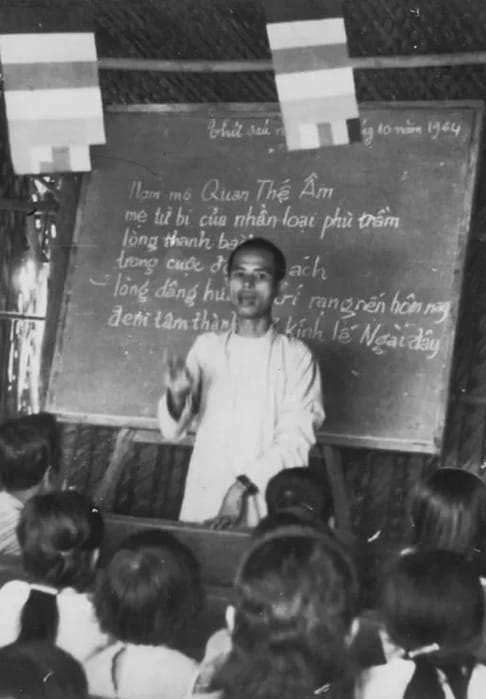

While completing the formalities of his education, Thay published his first book on Buddhism, Oriental Logic in 1950 (published by Huong Que publishing house) — a discussion of Eastern logic in the light of Aristotle, Hegel, Marx, and Engels. He also continued with initiatives to renew Buddhism and apply Buddhist teachings to the issues and challenges of his time. He was invited to Da Lat, up in the Central Highlands north of Saigon, to edit a Buddhist magazine and train young monks. There he began to publish a new kind of book for lay Buddhists, proposing ways to apply the teachings in daily family life, beyond just offering incense and prayers.

For the Lunar New Year of 1952 in Da Lat, Thay directed his students in his adaptation of the theatrical farce Le Tartuffe by Molière — later published with the title Cau Dong. Reflecting later on this time, Thay wrote, “I was full of creative energy, an artist, and a poet. More than anything else, I wanted to help renew Buddhism in my country, to make it relevant to the needs of the young people.”

The stories in this section are compiled from the following sources: Thich Nhat Hanh’s books, Inside the Now: Meditations on Time (2015) and Cultivating the Mind of Love (1996), and his Dharma Talk in Hanoi 6 May, 2008.

Additional sources include: Tieu su danh tang Viet Nam the ky XX (1995) (“Biographies of Renowned Vietnamese Monks of the Twentieth Century”), compiled by Venerable Thich Dong Bon, published by the Buddhist Association of Ho Chi Minh city; Nhat Hanh, La Phat Tu (“Being Buddhist,” 1953), published by Huong Que and Nhat Hanh; and Gia Dinh Tin Phat (“Buddhist Families,” 1953), published by Duoc Tue — a collection of articles first printed in the magazine Huong Thien in Dalat in 1951.

A Turbulent Time

In July 1954, following the Geneva Accords, which officially ended hostilities between the French and the Viet Minh, Vietnam was divided into two. The North became communist and the South soon became anti-communist, supported by the U.S. The separation of the country ushered in a turbulent time, with huge numbers migrating from North to South, in an atmosphere of confusion and uncertainty. To strengthen their voice and collect their energy, Buddhist leaders formed a National Buddhist Association in 1951 (Tổng Hội Phật Giáo Việt Nam) of all the schools and lineages in the South.

The board of the An Quang Institute invited Thay back to Saigon to help stabilize and renew the program of studies and practice for the young generation of monks and nuns, many of whom were drawn to Marxist ideals; or, feeling that Buddhist courses were neither rigorous nor relevant, were drawn by the promise of diplomas in secular professions, like medicine or engineering. Thay was charged with creating a more relevant and inspiring Buddhist program, which would also, for the first time, offer them a diploma comparable to secular courses.

While teaching at An Quang, Thay took the baccalauréat exams at Vuong Gia Can High School in Saigon, and in 1954 was accepted into the first cohort at the newly-opened Faculté des Lettres de l’Université de Saigon. He completed his university studies while continuing to teach and publish his own poems, articles, and books, and was awarded a BA in French and Vietnamese Literature. He also continued to write and publish his own poems, articles and books.

Thay’s time at the An Quang Institute was chronicled in the unpublished memoirs of Tri Khong.

Creating a Renewed, Engaged Buddhism

In 1955, the regime of Vietnamese Catholic leader Ngo Dinh Diem began to consolidate power, using every means possible. Catholics were explicitly favoured and Buddhists increasingly suppressed and marginalized. Hopes for democratic elections soon faded as guerrilla fighters continued to gain ground, and the government — under foreign influence — did everything they could to stymie a free ballot.

According to Thay’s private papers (published in 1955) he was asked to write a series of ten high-profile articles for the politically-neutral daily newspaper, Democracy (Dân Chủ). They asked him to show the strength of Vietnam’s own Buddhist heritage, and prove that Buddhism was not irrelevant or obsolete, as many were claiming.

And so, in the turmoil and pressure of the division of the country, Thay’s vision for engaged Buddhism crystallised. Published on the front page, under the pen name Thac Duc, and entitled Dao Phat Qua Nhan Thuc Moi (A Fresh Look at Buddhism), Thay’s daring articles proposed a new way forward in terms of democracy, freedom, human rights, religion, and education. They sent shock-waves across the country.

The tenth and final article was a bold Buddhist critique of President Diệm’s doctrine of “personalism” — his alternative to liberalism and communism which every government employee was required to follow.

The story of Thay’s of writing for the Democracy newspaper was related, in part, in his 6 May, 2008 Dharma Talk

A Home Visit and Continued Authorship

According to Thay’s unpublished private papers, he made his first trip back to Hue, to his home temple and family in 1955 — seven years after leaving. He received a warm welcome at his Root Temple and at the Bao Quoc Institute they organized a talk for him with the students. Thay also enjoyed a happy visit with his parents. It would be the last time he saw his mother in good health.

As his recognition and standing grew, in 1956 Thay was appointed Editor in Chief of Vietnamese Buddhism (Phat Giao Viet Nam), the official magazine of the new National Buddhist Association. He used a dozen pseudonyms to author articles on Vietnamese history, international literature (including Tolstoy, Albert Camus, Victor Hugo), philosophy, Buddhist texts, current affairs, short stories, and even folk poetry — doing everything he could to promote reconciliation and a spirit of togetherness between Buddhists of North and South.

He dug deep into Vietnam’s own history to propose a truly Vietnamese way out of the situation, drawing on the very engaged role Buddhism had played during the Trần and Lý Dynasties between the 11th and 13th Centuries, that had so inspired him as a young monk.

Thay’s pseudonyms included Hoàng Hoa (poetry), Thạc Ðức (philosophy, Engaged Buddhism, current affairs and reconciliation), Nguyễn Lang, (history of Buddhism), Dã Thảo (renewing Buddhism, role of Buddhism in society, influence of Buddhism on Western philosophy; critique of Buddhist institutions), Tâm Kiên (modern folk poetry), Minh Hạnh (literary commentary, French literature, cultural critiques), Phương Bối (deep Buddhism, message to youth), B’su Danglu (renewed Buddhism), Tuệ Uyển (Buddhist ethics), Minh Thư and Thiều Chi (Buddhism, short stories, interviews with leading monks). He edited as Nhất Hạnh, and also wrote Buddhist commentary and some poems as Nhất Hạnh.

An Experimental Community

Towards the end of 1956, Thay began to spend more time in B’lao, a remote tea-growing region in the central highlands. There, he retreated to a small thatched hut built among the tea trees in the grounds of Phưoc Hue Temple. It was a simple hut, at the end of a little path through the tea plantation, with just a bed and a table — and stacks of books.

Thay dreamed of creating a monastic community there in the mountains, and was soon joined by a number of young monastic brothers and students from An Quang and BAo Quoc. It was from here that he wrote and edited articles for the national Vietnamese Buddhism magazine over the next two years, while teaching the young monks. And it was also here that Thay had a memorable dream, recorded in his writings, in which he saw his late mother.

On 7 August, 1957, Thay and his friends found sixty acres of land available to buy from K’Briu and K’Broi in the heart of the Dai Lao Forest, in a quiet spot near the Montagnard village of B’su Danlu, about 10km from B’lao and Phuoc Hue Temple. In January 1958 they began clearing the land, and that summer started erecting some simple wooden structures.

They called this new community “Phuong Boi” (Fragrant Palm Leaves), after the name of Thay’s hut in the tea field of Phuoc Hue. Thay recalled that Phuong Boi “offered us her untamed hills as an enormous soft cradle, blanketed with wildflowers, grasses, and forest. Here, for the first time, we were sheltered from the harshness of worldly affairs.

With this new dream of a “rural practice center” Thay definitively broke free of the mould of the traditional Buddhist temple with its ceremonies and rituals, and created an environment exclusively dedicated to spiritual practice, study, healing, music, poetry, and community-building. They enjoyed sitting meditation in the early morning, tea meditation in the afternoons, and sitting meditation in the evenings. Phuong Boi was an experimental model for the renewal and reinvigoration of Buddhism. Though few may have foreseen it, Phuong Boii became a prototype for Thay’s many “mindfulness practice centers” that would flourish around the world by the end of the century.

Thay put great effort into editing Vietnamese Buddhism magazine. But in 1958, after just two years of publication, its funding was discontinued. Thay felt that it wasn’t just about a lack of funds, but also resistance in the Buddhist hierarchy to his bold articles. He felt he had failed in his effort to renew and unify Vietnamese Buddhism.

Stories in the section were related in Thich Nhat Hanh’s book Fragrant Palm Leaves (1999).

Waning Hope

With the Vietnamese Buddhism setback, still grieving his mother’s death, and enduring the painful division of the country, Thay struggled to keep his hope alive. He fell sick and was hospitalized for almost a month in Grall Hospital in Saigon, where he was treated by French doctors. His body was weak and he suffered from chronic insomnia. Even the doctors were unable to help, and his spirits were lower than ever.

Thay later described this period as a time of deep depression. In a Dharma Talk in Plum Village, on 20 June, 2014 Thay said “…after my mother died, and the country [had been] divided, and the war continued, I had depression… The doctors could not help. It was by the practice of mindful walking and mindful breathing that I could heal myself.

When you practice sitting or walking, you can know whether your breathing is healing or not. You can see the effect of healing right away when you breathe in. And when you walk, if every step brings you happiness and joy, …that is very nourishing and healing, and you know it. And with your depression, if you breathe and walk like that for one week, I know that you can transform. That is the practice of stopping and healing — stopping the running, stopping the fact that you are being carried away. You resist, you do not want to be carried away; you want to live your life, and you have your [own] insight as to how to do it.”

Awakening Intuition

Thay had the intuition that, if only he could master his full awareness of breathing and walking, he would be able to truly heal. It was the very challenges of the 1950s that forged the deepening of Thay’s personal practice, and gave him the spiritual strength he needed to find a way forward.

As a young monk, Thay studied the principle of counting and following the breath and trained in formal slow walking meditation (kinh hành). But Buddhist Institutes in Vietnam did not teach an applied meditation practice for personal healing; only meditation theory. And so, faced with deep suffering, Thay had to discover for himself a healing way to meditate. He experimented with a new method to combine his breath and steps more naturally while walking and, instead of counting only the breath, he counted the steps in harmony with the breath. With this concentration he was able to tenderly embrace his pain and acute despair without being swept away by strong feelings. “With the practice of mindful breathing,” he said, “I got out of the situation.”

He began this practice at An Quang and continued to experiment with it in B’lao and at Phuong Boi, and later at Princeton University in the US; and over the coming decades as his understanding of the sutras on meditation and breathing deepened.

The information in this section is compiled from a Q&A in Plum Village, on 25 July, 2013 and from Thich Nhat Hanh’s unpublished private papers.

New Hope

In spring 1959, known for his work as the Editor of Vietnamese Buddhism magazine, Thay was invited to attend the international Buddha’s birthday celebrations in Japan. Although his health was still weak (for part of the trip he was hospitalized in Tokyo), it proved to be an important journey that expanded his horizons. It was Thay’s first trip outside of Vietnam and the first to expose him to the network of the wider Buddhist community, who had gathered from around the world. From the other delegates, Thay heard about the great Buddhist collections in libraries in the west; and he realised the importance of learning English. On his return, he resolved to master the language within a year.

In November 1959, at a weekly lecture series he started giving for Saigon university students at Xa Loi Temple, Thay met many young people eager to help him in his work. Among them was Cao Ngoc Phuong, a young biology student, who became one of his “Thirteen Cedars,” a group of passionate young activists who studied with him and supported his vision for a modernized Buddhism.

Known simply as “Phuong,” Cao Ngoc Phuong was already actively leading social work programs in the Saigon slums and urged Thay to develop spiritual practices that could support such engaged action. He accepted the challenge, and it was in the process of guiding Phuog and “the thirteen cedars,” in social work, education, and relief projects, that Thay’s teaching — captured in his articles, books, and lectures — found its practical application and field of action for the first time. As Thay reflected later, “It was not easy because the tradition does not directly offer Engaged Buddhism. So we had to do it by ourselves.”

Phuong went on to become his principal collaborator over the next six decades, later becoming known as Sister Chan Khong — today a renowned and much-loved teacher in her own right.

The story of Thay first meeting Sister Chan Khong comes from a Shambhala Sun interview published 1 July, 2003.

Walking His Path

We invite you to continue reading Thay’s story as he’s invited to study in the U.S., engages in the peace movement in Vietnam, establishes the Order of Interbeing, meets with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., travels the globe to call for peace, and more.

Turn Your Inbox into a Dharma Door

Subscribe to our Coyote Tracks newsletter on Substack to receive event announcements, writing, art, music, and meditations from Deer Park monastics.

Support Deer Park

Donations are our main source of support, so every offering is greatly appreciated. Your contribution helps us to keep the monastery open to receive guests throughout the year.